Rienforcement learning

Introduction

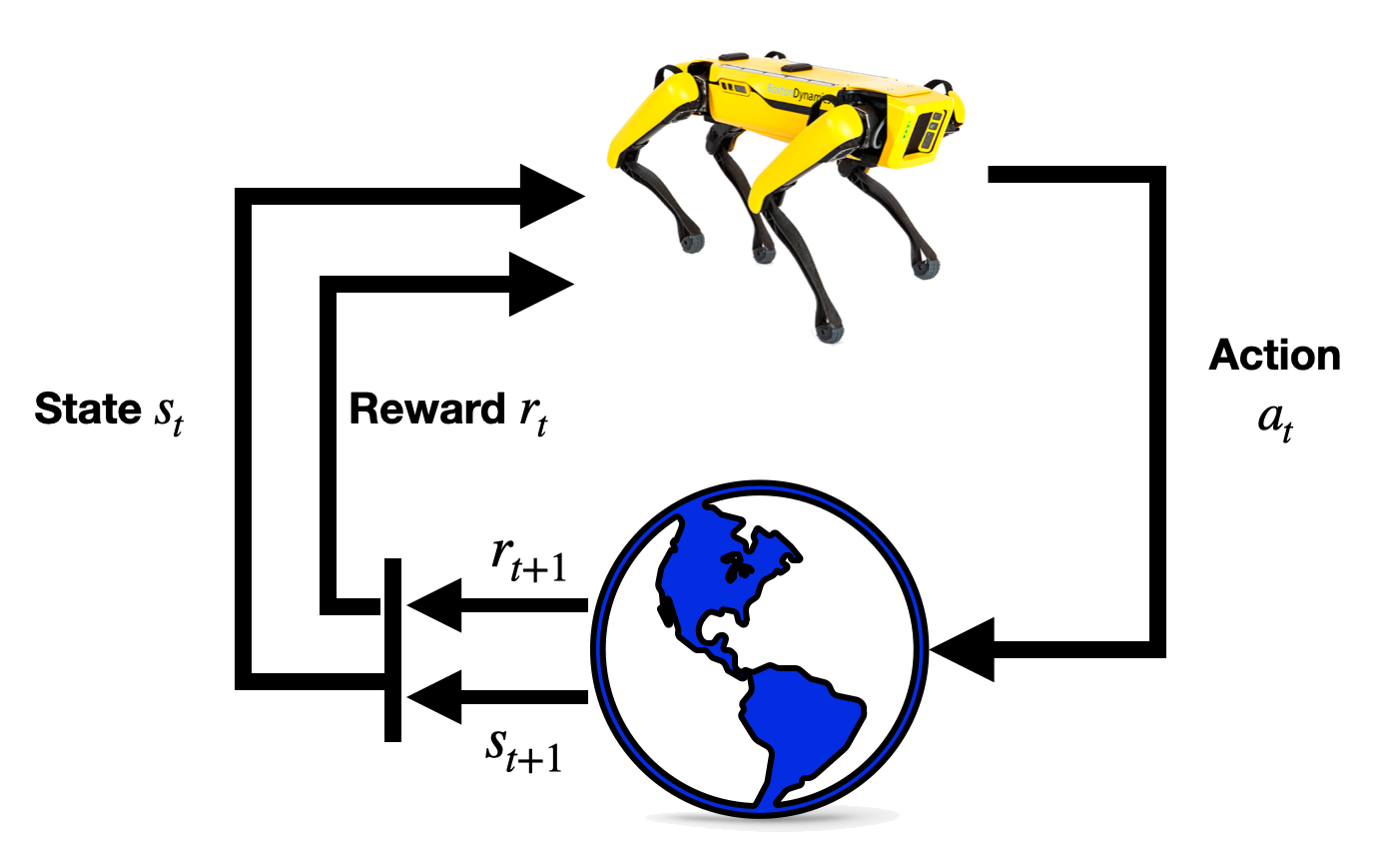

Reinforcement learningis learning from experience.

Reinforcement learning is a branch of machine learning in which agents learn to make sequential decisions in an environment, guided by a set of rewards and penalties.

It differs from traditional supervised machine learning in a few ways, primarily:

-

Experience instead of labels: In traditional supervised machine learning, we need to provide examples that contain inputs and labelled outputs. In reinforcement learning, the “labels” are provided by the environment when the agent interacts with the environment. These “labels” are called rewards. Rewards can be positive, which means our agent will try to learn behaviour that leads to positive rewards, or rewards can be negative, which means out agent will try to learn behaviour that leads to negative rewards. The aim is to learn behaviour that increases the cumulative reward over a number of decisions.

-

Decisions are sequential: Reinforcement learning is sequential decision making. This means that our agent needs to make a series of decisions over time, which each decision affecting future outcomes. Feedback, in the form of positive/negative rewards, is received at each step (although the reward may be zero at most steps), but in most situations, simply maximising feedback at each step is not optimal — our agent needs to consider how each action affects the future.

Overview

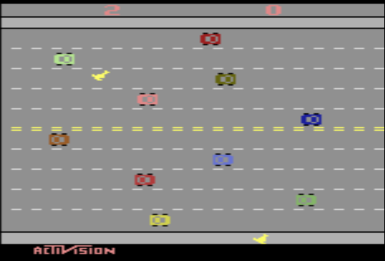

Before we start on the basic of reinforcement learning, let’s build an example of a reinforcement learning agent. We will use reinforcement learning to play Atari games. Atari was a game consoles manufacturer in the 1990s – their logo is shown in Fig.

The Arcade Learning Environment, built on the Atari 2600 emulator Stella, is a framework for reinforcement learning that allows people to experiment with dozens of Atari games. It is built on the popular Gymnasium framework from OpenAI.

Example 1

As an example we mention Freeway is the Atari 2600 game that we will begin with. In Freeway, a chicken needs to cross several lanes on a freeway without being run over by a car. A screenshot of the game is shown in previous Fig. Each time the chicken crosses to the top, we gain one point. If the chicken is struck by a vehicle, it goes back a few spaces, slowing it down. The aim is to cross the road as many times as possible in the allocated time.

Here is the behavior of a trained aganet (right) and a completely random agent (left).

Example 2: Playing Frogger

Let’s build another one, but this time, to play the game Frogger. This is a very similar game. Instead of a chicken, there is a frog. The frog has to get to the other side of a road and river. If the frog is struck by a vehicle, it loses a life and starts back at the begging. Once it gets to the river at the top, it needs to jump on the logs and other floating debris to get to the other side of the river. If it falls into the water, it loses a life and starts back at the begging. It has three lives in total.

Markov Decision Processes

A Markov Decision Process (MDPs) is a framework for describing sequential decision making problems. In machine learning, problems such as classification and regression are one-time tasks. That is, a classification/regression model is given an input and returns an output. Then, the next input it is given it entirely independent from the first. In sequential decision making problems, we need to make a series of decisions over time, in which each decision influences the possible future. For example, navigating from one place to another requires us to choose a direction and velocity, move in that direction at the velocity, and then make this decision again and again until we reach our destination. So, even at that first step, we have to consider how each move affects the future. As another example, a clinician making medical treatment decisions has to consider whether decisions taken today will impact future decisions about their patients.

In the language of reinforcement learning, we say that the decision maker is the agent, and their decisions are actions that they execute in an environment or state.

Techniques like heuristic search and classical planning algorithms assume that action are deterministic – that is, before an agent executes an action in a state, it knows that the outcome of the action will be. MDPs remove the assumption of deterministic events and instead assume that each action could have multiple outcomes, with each outcome associated with a probability. If there is only one outcome for each action (with probability 1), then the problem is deterministic. Otherwise, it is non-deterministic. MDPs consider stochastic non-determinism; that is, where there is a probability distribution over outcomes. Here are some examples of stochastic actions:

-

Flipping a coin has two outcomes: heads (0.5) and tails (0.5)

-

Rolling two dices together has twelve outcomes: 2 (1/36), 3(1/18), 4(3/36)….12(1/36)

-

When trying to pick up an object with a robot arm, there could be two outcomes: successful (4/5) and unsuccessful (1/5)

-

When we connect to a web server, there is a 1% chance that the document we are requesting will not exist (404 error) and 99% it will exist.

-

When we send a patient for a test, there is a 20% the test will come back negative, and an 80% chance it will come back positive.

MDPs have been successfully applied to planning in many domains:

- Robot navigation.

- Planning which areas of a mine to dig for minerals.

- Treatment for patients.

- Maintenance scheduling on vehicles, and many others.

Definition

A Markov Decision Process (MDP) is a fully observable, probabilistic state model. The most common formulation of MDPs is a Discounted-Reward Markov Decision Process. A discount-reward MDP is a tuple $(S, s_0, A,P, r, \gamma)$. containing:

- $S$ is the state space.

- $s_0 \in S$ is the initial state.

- Actions $A(s)\subset A$ applicable in each state $s\in S$ that our agent can execute.

-

Transition probability $P_a(s^{‘} s)$ for $s in S$ and $a in A(s)$ - rewards $r(s, a, s^{‘})$ positive or negative rewards from transitioning from state $s$ to state $s^{‘}$ using action $a$

- Discount factor $0 \leq \gamma < 1$.

Let’s break down the above points in model detail.

States are the possible situations in which the agent can be in. Each state captures the information required to make a decision. For example, in robot navigation, the state consists of the position of the robot, the current velocity of the robot, the direction it is heading, and the position of obstacles, doors, etc. In an application for scheduling maintenance on vehicles for a delivery company, the state would consist of vehicle IDs, vehicle properties such as make, maximum load, etc., location of vehicles, number of kilometres since their last maintenance check, etc.

Actions allow agents to affect the environment/state — that is, actions transition the environment from one state to another. They are also the choices that are available to an agent in each state: which action should I choose now? For now, we assume that the agent is the only entity that can affect a state. As noted above, an action can have multiple possible outcomes. Exactly one outcome will occur, but the agent does not know which one until after the action is executed.

Transition probabilities tell us the effect(s) of each action, including the probabilities of each outcome. For example, in the vehicle maintenance task, when our agent schedules a vehicle to be inspected, possible outcomes could be: (a) no further maintenance required (80% chance); (b) minor maintenance required (15% chance); or (c) major maintenance required (5% chance).

Rewards specifies the benefit or cost of executing a particular action in a particular state. For example, a robot navigating to its destination receives a positive reward (benefit) for reaching its destination, a small negative reward (cost) for running into objects on the way; and a large negative reward for running into people.

The discount factor determines how much a future reward should be discounted compared to a current reward.

For example, would you prefer 100 today or 100 in a year’s time? We (humans) often discount the future and place a higher value on nearer-term rewards.

Assume our agent receives rewards $(r_1, r_2, r_3,r_4,\ldots)$in that order. If is the discount factor, then the discounted reward is:

\[V = r_1 + \gamma r_2 + \gamma^2 r_3 + \gamma^3 r_4\]if $V_t$ is the value received at time $t$, then $V_t = r_t + \gamma V_{t+1}$. So the futher away the reward from the state $s_0$, the less actual reward we will receive from it.

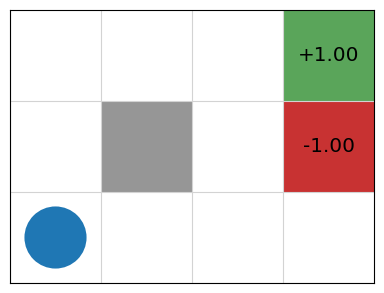

Grid World

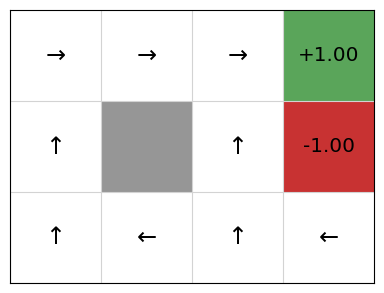

An agent is in the bottom left cell of a grid. The grey cell is a wall. The two coloured cells give a reward. There is a reward of 1 of being in the top-right (green) cell, but a negative value of -1 for the cell immediately below (red).

-

If the agent tries to move north, 80% of the time, this works as planned (provided the wall is not in the way)

-

10% of the time, trying to move north takes the agent west (provided the wall is not in the way);

-

10% of the time, trying to move north takes the agent east (provided the wall is not in the way)

-

If the wall is in the way of the cell that would have been taken, the agent stays in the current cell.

The task is to navigate from the start cell in the bottom left to maximise the expected reward. What would the best sequence of actions be for this problem?

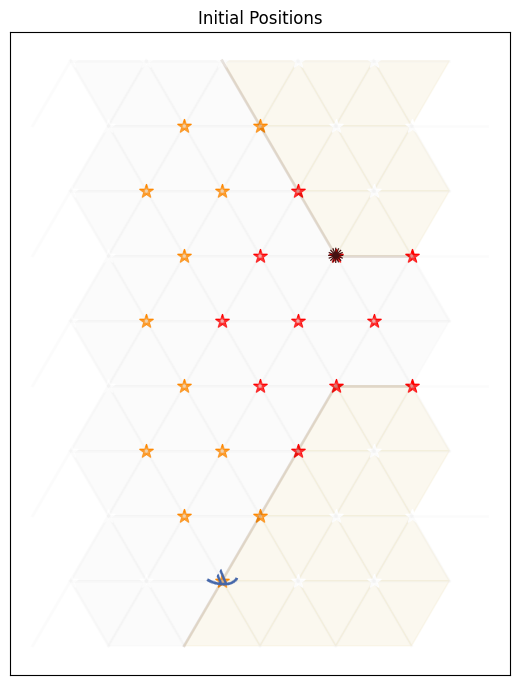

Contested Crossing

An agent (a ship), denoted using ; is at the south shore of a body of water. It may sail between points on the hexagonal grid where the terrain is water (pale grey), but not on land (pale yellow), choosing a different direction at each step (West, North-West, North-East, East, South-East or South-West). There is a reward of 10 for reaching the north shore, but a negative value of -10 for sinking on the way.

At the closest point of the north shore is an enemy, denoted using the ✺ character. The enemy will shoot at the ship when it is in areas of danger (yellow or red stars). It will do so once for each step. Therefore, the enemy’s behaviour is completely determined and no choice needs to be made.

-

In locations with yellow or red stars, the ship may also shoot at the enemy, but it cannot do so and turn at the same time. If it chooses to shoot, it will continue sailing in the same direction.

-

In areas of low danger (yellow), a shot will damage the target 10 of the time (either the ship firing at the enemy, or the enemy firing at the ship).

-

In areas of high danger (red), a shot will damage the target 99 of the time.

-

When the ship is damaged, it has a chance of failing to move in its step. At full health, the ship moves successfully 100 of the time, with damage level 1 it moves successfully 67 and at damage level 2, 33; and at damage level 3 , it sinks.

-

When the enemy is at damage level 1, there is no change in its behaviour. When it is at damage level 2 it is destroyed. At this point the ship is in no further danger.

-

The ship can observe the the entire state: it’s location, the enemy location, it’s own health, and the health of the enemy.

In this task, the agent again has the problem of navigating to a place where a reward can be gained, but there is extra complexity in deciding the best plan. There are multiple different high reward end states and low reward end states. There are paths to the reward which are slow, but guarantee achieving the high reward, and there are other paths which are faster, but more risky.

MDPs can also be expressed as code, rather than just as a model. An algorithm for solving the MDP creates an instance of a class and obtains the information that it requires to solve it.

class MDP:

""" Return all states of this MDP """

def get_states(self):

abstract

""" Return all actions with non-zero probability from this state """

def get_actions(self, state):

abstract

""" Return all non-zero probability transitions for this action

from this state, as a list of (state, probability) pairs

"""

def get_transitions(self, state, action):

abstract

""" Return the reward for transitioning from state to

nextState via action

"""

def get_reward(self, state, action, next_state):

abstract

""" Return true if and only if state is a terminal state of this MDP """

def is_terminal(self, state):

abstract

""" Return the discount factor for this MDP """

def get_discount_factor(self):

abstract

""" Return the initial state of this MDP """

def get_initial_state(self):

abstract

""" Return all goal states of this MDP """

def get_goal_states(self):

abstract

Policies

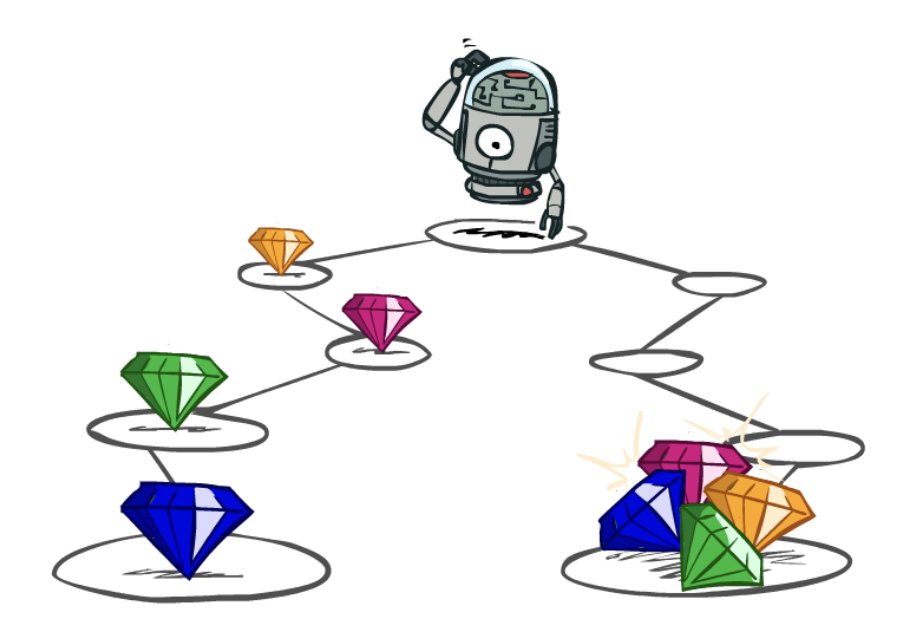

The planning problem for discounted-reward MDPs is different to that of classical planning or heuristic search because the actions are non-deterministic. Instead of a sequence of actions, an MDP produces a policy.

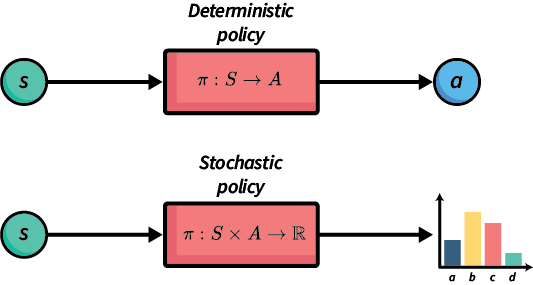

A policy is a function that tells an agent which is the best action to choose in each state. A policy can be deterministic or stochastic.

We can differentiate between two types of policies.

Deterministic vs. stochastic policies

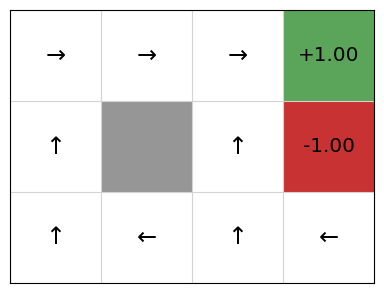

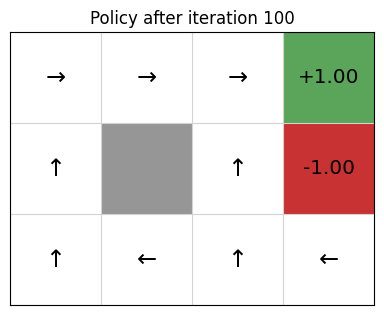

A deterministic policy $\pi: S\rightarrow A$ is a function that maps states to actions. It specifies which action to choose in every possible state. Thus, if we are in state $s$ , our agent should choose the action defined by $\pi(s)$. A graphical representation of the policy for Grid World is:

So, in the initial state (bottom left cell), following this policy the agent should go up. If it accidentally slips right, it should go left again to return to the initial state.

Of course, agents do not work with graphical policies. The output from a planning algorithm would be a dictionary-like object or a function that takes a state and returns an action.

To execute a stochastic policy, we could just take the action with the maximum $\pi(s,a)$ . However, in some domains, it is better to select an action based on the probability distribution; that is, choose the action probabilistically such that actions with higher probability are chosen proportionally to their relative probabilities.

Optimal Solutions for MDPs

For discounted-reward MDPs, optimal solutions maximise the expected discounted accumulated reward from the initial state $s_0$. But what is the expected discounted accumulated reward?

\[V^{\pi}(s) = E_{\pi}\big[\sum_i \gamma^{i} r(s_i, a_i, s_{i+1}\;|\; a_i = \pi(s_i) \big]\]The expected discounted reward from $s$ for a policy $\pi$ is

Bellman equation

The Bellman equation, identified by Richard Bellman, describes the condition that must hold for a policy to be optimal. The Bellman equation is defined recursively as:

\[V(s) = \max_{a\in A(s)} \sum_{s^{'}\in S}P_a(s^{'}|s)\left[ r(s,a,s^{'}) + \gamma V(s^{'})\right]\]First, we calculate the expected reward for each action. The reward of an action is the sum of the immediate reward for all states possibly resulting from that action plus the discounted future reward of those states. The discounted future reward is the $\gamma$(discount reward) times the value of $s^{‘}$ , where $s^{‘}$ is the state that we end up in. However, because we can end up in multiple states, we must multiple the reward by the probability of it happening: $P_a( s^{‘}|s)$.

Bellman equations can be described slightly differently, using what are known as

Q-values.

The Q-value for action $a$ in state is defined as:

\[Q(s,a) = \sum_{s^{'} in S}P_a(s^{'}|s)\left[r(s, a, s^{'}) + \gamma V(s^{'})\right]\]This represents the value of choosing action $a$ in state $s$ and then following this same policy until termination. . Now the value of a node becomes

\[V(s) =\max_{a \in A(s)} Q(s,a)\]Policy Extraction

Given a value function $V$, how should we then select the action to play in a given state? It is reasonably straightforward: select the action that maximises our expected utility!

So, if the value function $V$ is optimal, we can select the action with the highest expected reward using:

\[\pi(s) = \text{argmax}_{a\in A(s)}Q(s,a)\]Value-based methods

Techniques for solving MDPs can be separated into three categories:

-

Value-basedtechniques aim to learn the value of states (or learn an estimate for value of states) and actions: that is, they learn value functions or Q functions. We then use policy extraction to get a policy for deciding actions. -

Policy-basedtechniques learn a policy directly, which completely by-passes learning values of states or actions all together. This is important if for example, the state space or the action space are massive or infinite. If the action space is infinite, then using policy extraction as defined in Part I is not possible because we must iterate over all actions to find the optimal one. If we learn the policy directly, we do not need this. -

Hybrid techniquesthat combine value- and policy-based techniques.

In this section, we investigate some of the foundational techniques for value-based reinforcement learning, and follow up with policy-based and hybrid techniques in the follow chapters.

Value Iteration

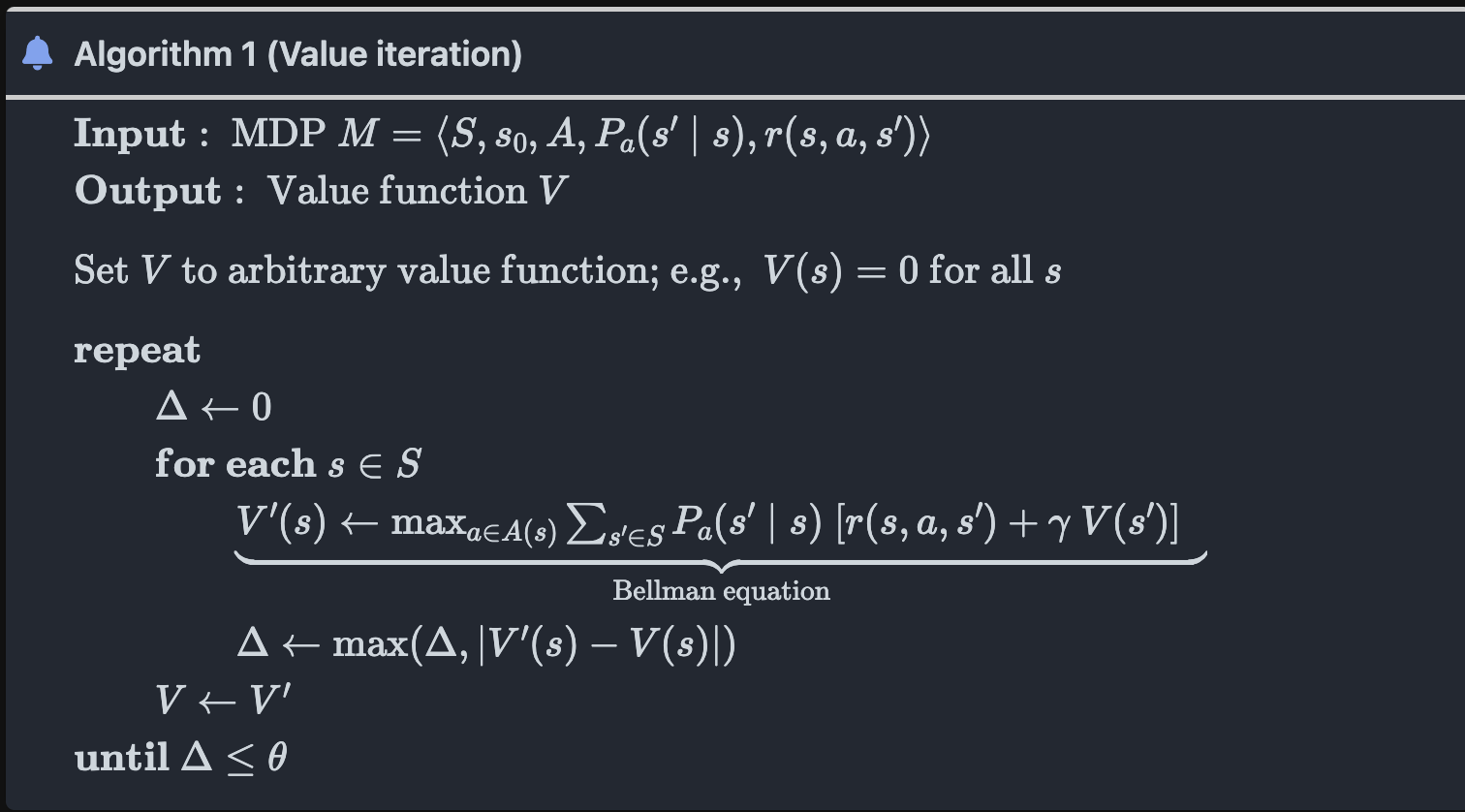

Value Iteration is a dynamic-programming method for finding the optimal value function $V^{\star}$

by solving the Bellman equations iteratively. It uses the concept of dynamic programming to maintain a value function $V$

that approximates the optimal value function $V^{\star}$

, iteratively improving

until it converges to

(or close to it).

Once we understand the Bellman equation, the value iteration algorithm is straightforward: we just repeatedly calculate $V$ using the Bellman equation until we converge to the solution or we execute a pre-determined number of iterations

Value iteration converges to the optimal policy as iterations continue: $V\rightarrow V^{\star}$ as $i\rightarrow \infty$ , where $i$ is the number of iterations. So, given an infinite amount of iterations, it will be optimal.

Value iteration converges to the optimal value function $V^{\star}$ asymptotically, but in practice, the algorithm terminates when the residual $\Delta$ reaches some pre-determined threshold $\theta$ – that is, when the largest change in the values between iterations is “small enough”.

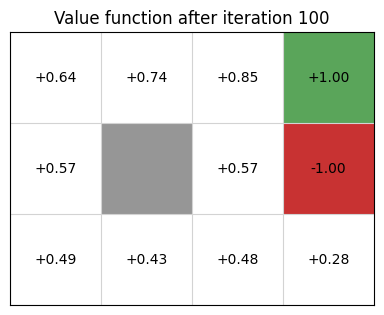

Example 1: Value Grid

here is the evolution of the cell values in the Grid World MDP.

After 100 itertions, here is the final optimal values.

Based on those values, we could extract the best policy:

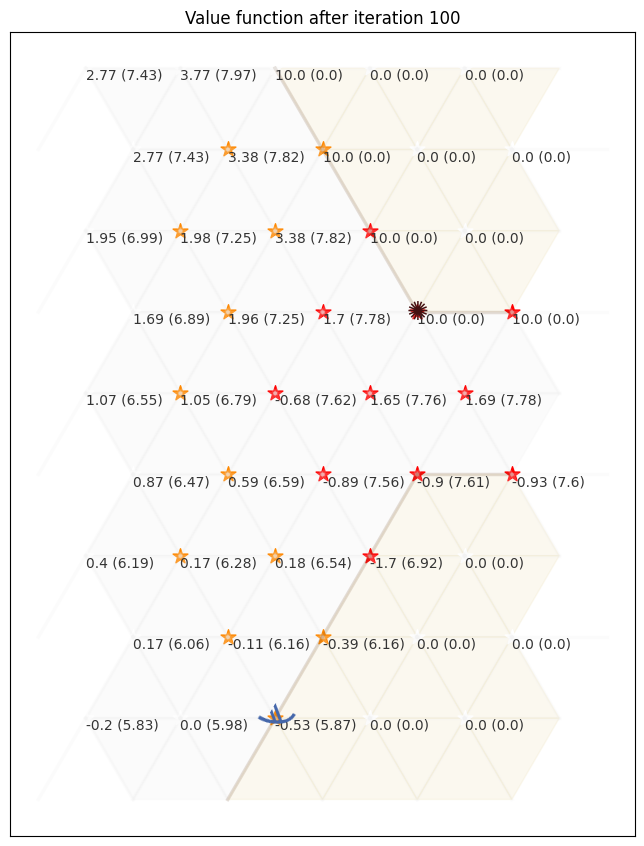

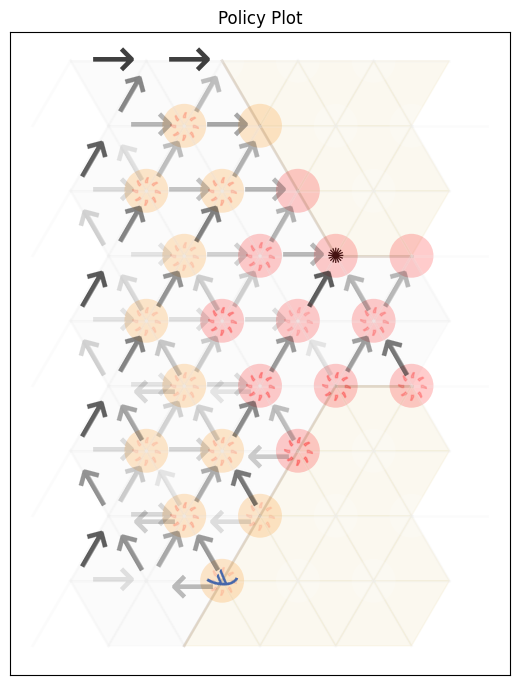

Example 2:Value iteration in Contested Crossing

The process works in exactly the same way for the Contested Crossing problem. However, in this case, the state space is no longer represented only by the coordinates of the agent. We also have to take into account non-locational information - damage to the ship, damage to the enemy, and the previous direction of travel - since these features will also affect the likelihood of the ship reaching its goal.

This can be difficult to visualise graphically. We can no longer simply assign one value to each physical location and so map the progress of the agent from each value to the largest adjacent one. We can, however, use other ways to get a general sense of how the state affects the behaviour of an agent at any one point. For instance, we can show the mean and standard deviation values for all states that are at a single location, as follows

And here is the best policy once the value iteration converges:

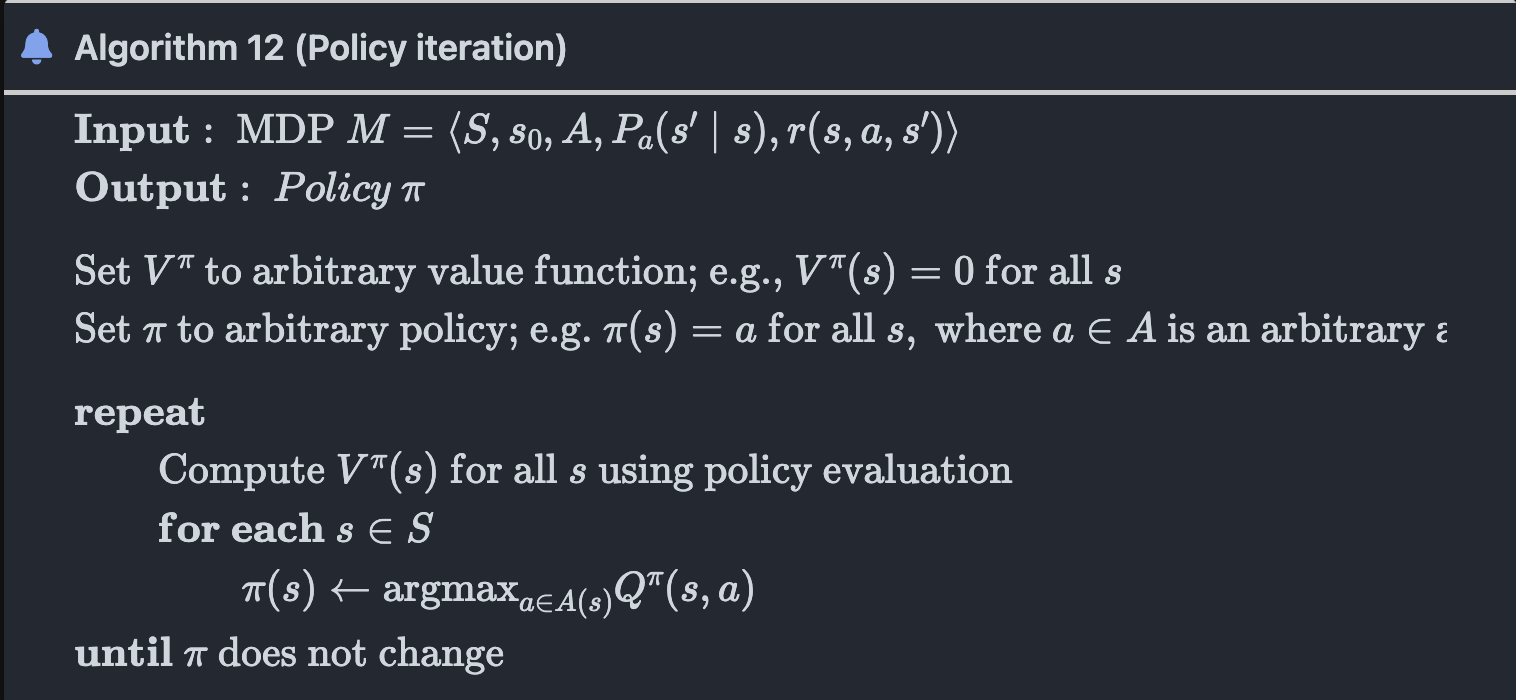

Policy-based methods

The other common way that MDPs are solved is using policy iteration – an approach that is similar to value iteration. While value iteration iterates over value functions, policy iteration iterates over policies themselves, creating a strictly improved policy in each iteration (except if the iterated policy is already optimal).

Policy iteration first starts with some (non-optimal) policy, such as a random policy, and then calculates the value of each state of the MDP given that policy — this step is called policy evaluation. It then updates the policy itself for every state by calculating the expected reward of each action applicable from that state.

The basic idea here is that policy evaluation is easier to computer than value iteration because the set of actions to consider is fixed by the policy that we have so far.

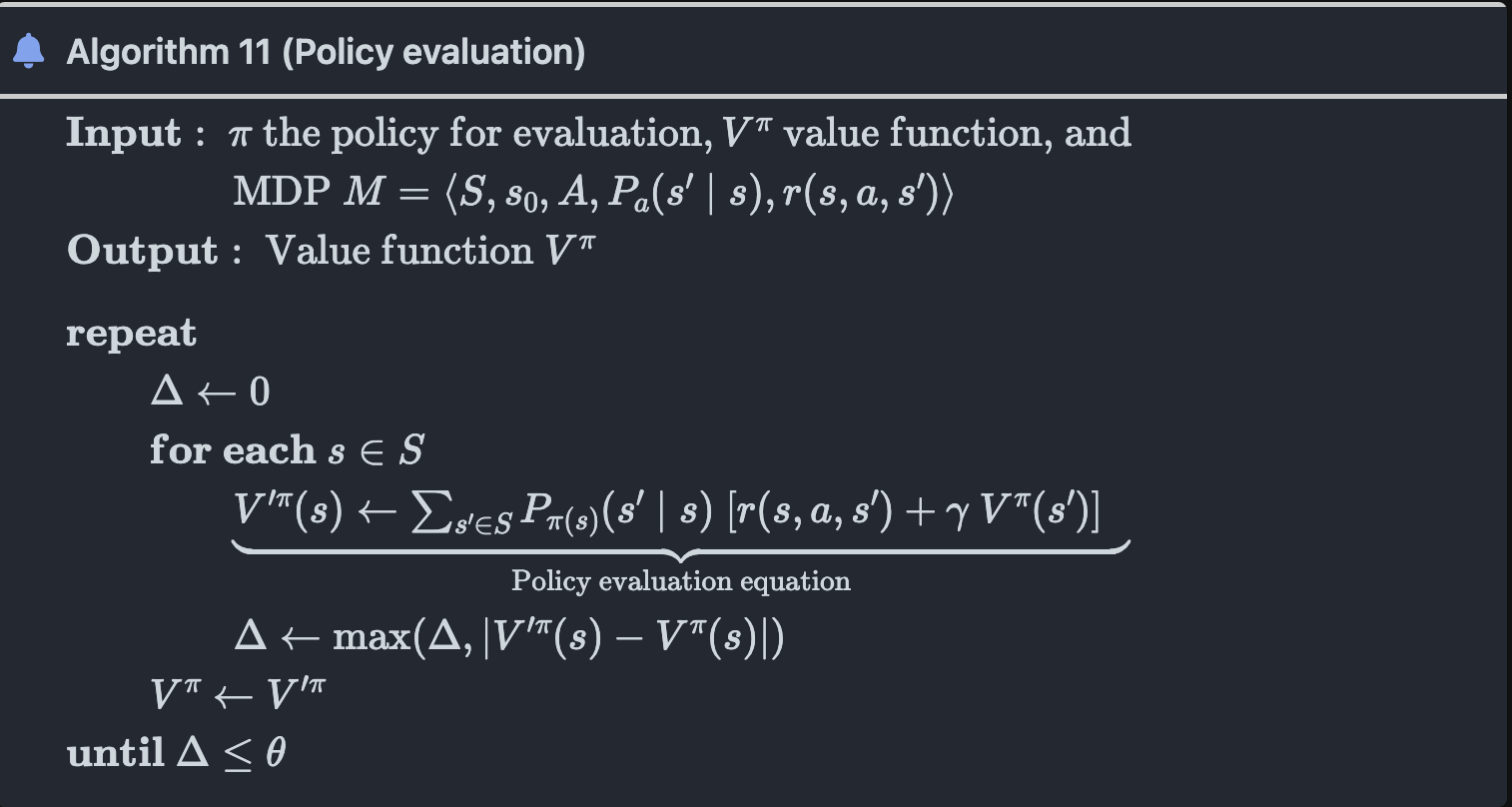

Policy evaluation

An important concept in policy iteration is policy evaluation, which is an evaluation of the expected reward of a policy.

The expected reward of policy $\pi$ from $s$, $V^{\pi}(s)$ , is the weighted average of reward of the possible state sequences defined by that policy times their probability given $\pi$. .

\[V^{\pi}(s) = \sum_{s^{'}\in S}P_{\pi(s)}(s^{'}|s)\left[r(s,a,s^{'}) + \gamma V^{\pi}(s^{'})\right]\]Policy evaluation can be characterised as $V^{\pi}(s)$ as defined by the following equation:

Once we understand the definition of policy evaluation, the implementation is straightforward. It is the same as value iteration except that we use the policy evaluation equation instead of the Bellman equation.

Policy Improvement

f we have a policy and we want to improve it, we can use policy improvement to change the policy (that is, change the actions recommended for states) by updating the actions it recommends based on $V(s)$ that we receive from the policy evaluation.

If there is an action $a$ such that $Q^{\pi}(s,a) > Q^{\pi}(s, \pi(s))$ , then the policy $\pi$ can be strictly improved by setting $\pi(s)\leftarrow a$ . This will improve the overall policy.

Pulling together policy evaluation and policy improvement, we can define policy iteration, which computes an optimal $\pi$ by performing a sequence of interleaved policy evaluations and improvements:

Let’s show this mechanis on the GridWorld MDP:

And here is the final graph after 100 iterations:

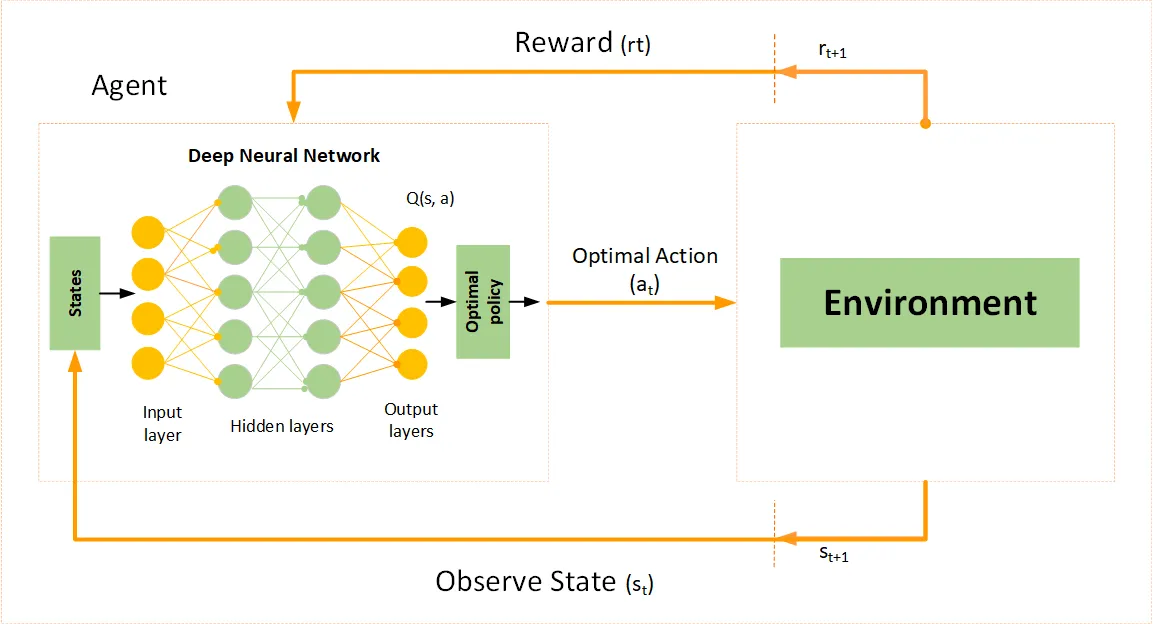

Deep Q-learning

Deep Q-Learning or Deep Q Network (DQN) is an extension of the basic Q-Learning algorithm, which uses deep neural networks to approximate the Q-values. Traditional Q-Learning works well for environments with a small and finite number of states, but it struggles with large or continuous state spaces due to the size of the Q-table. Deep Q-Learning overcomes this limitation by replacing the Q-table with a neural network that can approximate the Q-values for every state-action pair.

Here are the key-concepts of Q-learning:

-

Q-Function Approximation: Instead of using a table to store Q-values for each state-action pair, DQN uses a neural network to approximate the Q-values. The input to the network is the state, and the output is a set of Q-values for all possible actions.

-

Experience Replay: To stabilize the training, DQN uses a memory buffer (replay buffer) to store experiences (state, action, reward, next state). The network is trained on random mini-batches of experiences from this buffer, breaking the correlation between consecutive experiences and improving sample efficiency.

-

Target Network: DQN introduces a second neural network, called the target network, which is used to calculate the target Q-values. This target network is updated less frequently than the main network to prevent rapid oscillations in learning.

In your homework you will implement a Deep Q learning algorithm using pytorch. Her is a link for a basic tutorial Playing CartPole